Being

Chartwell believes in the importance of creative visual thinking through the visual arts - a particularly accessible and dynamic way to explore the creative mind.

Thinking About Chartwell & Art

Exploring a Chartwell Philosophy

What is art?

Why is it important?

Why does working with public galleries matter?

For 50 years, the Chartwell Project has grappled with questions like these. In the process, Chartwell has developed a philosophy advocating for the importance of the visual arts. Over time, this philosophy has deepened to investigate the neurological, emotional and physical processes involved in art object making.

First and foremost, Chartwell is interested in the power of the ideation processes involved in both the making and the viewing of art objects and believes that the sense activated imagination needs to be more widely understood and valued. Creative thinking grounded in this empowering resource is primary and, aided by contemplative sense based intelligence, opens to the life-enhancing wonder of the spontaneous idea.

How do we describe an object as art?

Creative cognition is vital to the art object making and viewing experience and the domain of art is an exercise ground for the senses and imagination. Using the improvising imagination, art is creative thinking (both sentient and rational) within an aesthetic context, through making by the artist and perception by the viewer.

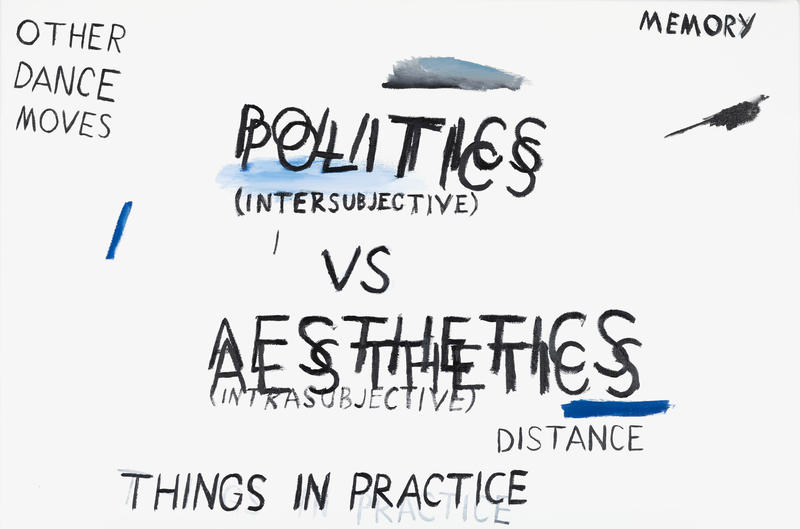

Politics vs aesthetics by Tahi Moore (2018), Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 2018

How do we look at art?

Much art seeks to be shared, to communicate, and there is a deliberate intention by the artist to stimulate the viewer’s perception of the work. This active relationship between the viewer and the artwork has always been of interest to Chartwell. The viewing of art reveals direct sensing energies and needs which drive the creative search for meanings. The process is more intense than commonplace practical looking and is before words. It involves both focussed and unfocussed modes of seeing analogically via simulation. Both the emotional and rational intelligence systems operate together/interactively. These processes of mind and body are those that distinguish humanity and its evolution.

Lucien Freud spoke perceptively about the viewing process, saying that ”the longer you look at an object, the more abstract it becomes, and, ironically, the more real.” Indeed, many find the viewing process seems to work like this:

- A fast look with the rational mind trying to find answers to questions like “What does it mean? Should I know about this?”

- When the reasoning mind gives up (or shows signs of frustration) a shift to slow and close contemplation of aesthetic forms. Here, the senses, imagination and memory start to work creatively.

- An open unfocused sensing submission to the whole work.

- An imaginative creative personal interpretation.

- A judgement based on both an intuitive and reasoned assessment of success in reconciling sensual and rational form and the felt affects in the viewing experience.

Encouraging us to be open to a sense of wonder, Rob writes about the viewing experience:

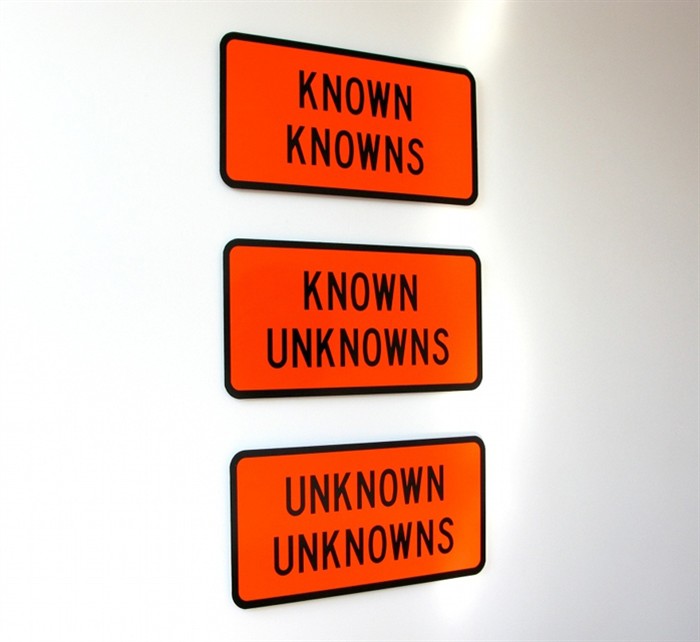

When ‘reading’ an art work, a deferral of meaning becomes a means to enhance the lived experience of being in front of the work. Ambiguities of forms and meanings promote creative responses and are an important component of the art object perceiving system. The elusive subject, recognised as a hook to the imagining enquiring mind and body, can help to encourage understandings that there need be no one immediate closure of meaning. We then are more open to poetic paradox, and a sense of wonder while also allowing an awareness of our own experience of internal perception to emerge. There are many works in the Chartwell Collection that engage in this enquiry around the reality of the unknowable, the unanswerable and the uncertain - delivering a stimulus for a personal, active, empathetic experience.

An acquisition of a work by John Reynolds, Known Knowns/Known Unknowns/Unknown Unknowns provides the very words which allude to these ideas:

Democratic Vistas, John Reynolds (2011), Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 2012

Art involves the heart, mind, body and mediums activated by intuition, invention and intellect. When we really see an artwork, we are participating with the mind that made it. We experience art through our own intuitive sensing, emotional, imagining body and our conscious, reasoning mind. Meanings arise from interactions between the artwork’s mediums, methods, and means of making, composition, emotional affects and from the ‘reading’ of any intellectual representations in the work.

“The perceiving mind creatively apprehends and reconciles these means of cognition to select practical, unified meanings including aesthetic values. Meanings are constructed by directly sensed data or by learning from others. Both of these systems create and use memory,” writes Rob Gardiner.

For Chartwell, these key investigations into making, meaning and perceiving remain the core of what we do. The Chartwell Project shares with many, a belief in the importance of creative visual thinking through the visual arts – a particularly accessible and dynamic way to explore the creative mind. Being, Seeing, Making and Thinking are key actions that the arts deliver in engaging with ourselves and the world. Art challenges and encourages us to be more introspective. As the New Zealand based philosopher of aesthetics, Denis Dutton wrote, “artworks create imaginative experiences for both the maker and the perceiver.”

COMMUNITY of the people / Nordic by Diena Georgetti, (2015), Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 2015

We do not live passively. From the earliest moments of cognition, the individual strives to understand self and the world. Chartwell explores these understandings via the visual arts, to reach towards unfamiliar things, to build memories, to add to experience, to a balance of reason and the senses – to illuminate a developing sense of self through the art experience. Much remains unknowable, purposeless, ambiguous, subjective and private. Glimpses, glances and fleeting, invented impressions influence our visual world. The range of responses remains immensely variable. As Philosopher Stephen T. Asma references in Evolution of Imagination (2017), there are two modes of imaginative enquiry and simulation at work – “that which is involuntary, instructive, spontaneous and unintentional and that which is voluntary, deliberate and intentional.”

Our intention and deep commitment to the contemporary visual art sector grows because, in this space, we most directly and readily perceive the mind-making influences of our time. Yet, the knowledge of the value of art does not translate well to the general public and so we work to deepen understanding of the broad habits of a creative mind for all, within education, within our personal lives and within the work place.

The Chartwell Collection has long had a focus on the formal and reductive within a wider discussion of modernism and post modernism from a 20th and 21st Century perspective. We are interested in representing the development of art practices, the sociology and psychology of art and aesthetics, the dynamics of form, the concretization of ideas, and the influences of mediums including context, time, space, and chance.

The Collection incorporates practices of interest including an exploration of the post- painterly, the object-ness (or thing-ness) of the artwork, an indebtedness to drawing and observable mark making, givens, found materials and especially works revealing process. The drawing collection, for example, represents a cluster of interests and sub-themes.

The Collection as a whole embodies access to the direct experience and understanding of ideas presented within the domain of materials, technologies and freedoms not previously so readily available to the artist or to the viewer. It has a depth of holdings, many iconic and numerous works by particular artists, and whilst the focus remains on New Zealand, Australian and Pacific works, some relevant international acquisitions take place where they can contribute to the overall philosophy. These are all understood as resources for curatorial use into the future.

Menlo Mana by Joe Sheehan, (2005), Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2005. Photo Credit: John Collie.

The visual arts operate via those functions of the mind which enable discovery of the discovery experience itself. Optical, tactile and spatial senses are primary as drivers in the visual arts. In the fast changing, innovative world in which we live, understanding the arts as a communal resource and creative stimuli is vital. Respecting and supporting creative artists underpins the growth of a community’s innovation capacities.

As Professor of Psychology at Boston College, Ellen Winner’s writes, “In the case of the visual arts, the kinds of habits of mind we can all develop include learning to observe closely, learning to envision, learning to explore and learning from mistakes, learning to stick with something over time and developing a critique and evaluation and reflection on one’s process.” (2019) We all know the benefits of making and doing – not only does this open and focus our minds, our observation skills are sharpened, and one’s potential for creating new ideas is maximised.

To encourage more participation in this process, Chartwell's Squiggla Project has been developed to centre on mark-making. As Rob Gardiner explained in 2019, “Mark making combines composing and performing as recorded, almost simultaneous events so the maker is both maker and first viewer of the work made. S/he is in a similar position to the conductor of an orchestra where, through gestural direction, the work is rendered. It is like a conversational relationship between medium and mark - with the marked object and the used tool both contributing means and meanings to the creation of the mark itself. It is easy to overlook the advantages of sustained mark making exercises that develop innate, generally under-utilised mind skills transferable to other domains of life’s experience and that can be a way to learn of the essences of creative thought and action. This goal is only fully understood through experience.”

“We know not through our intellect but through our experience.”

Maurice Merleau-Ponty

The value of the creative thinking processes within the arts is increasingly being recognised. The effect on the individual is measurable, in open-mindedness, curiosity, interest in others, general creativity, innovation, general intelligence, academic achievement, good health and fulfilment in life. The Chartwell Project aims to reveal a world open to the mysteries of expansive creative thought in the arts.