Rob Gardiner & Sue Gardiner on The Chartwell Trust | Interview with Brown Bread

By Jo Blair — 14 April 2019

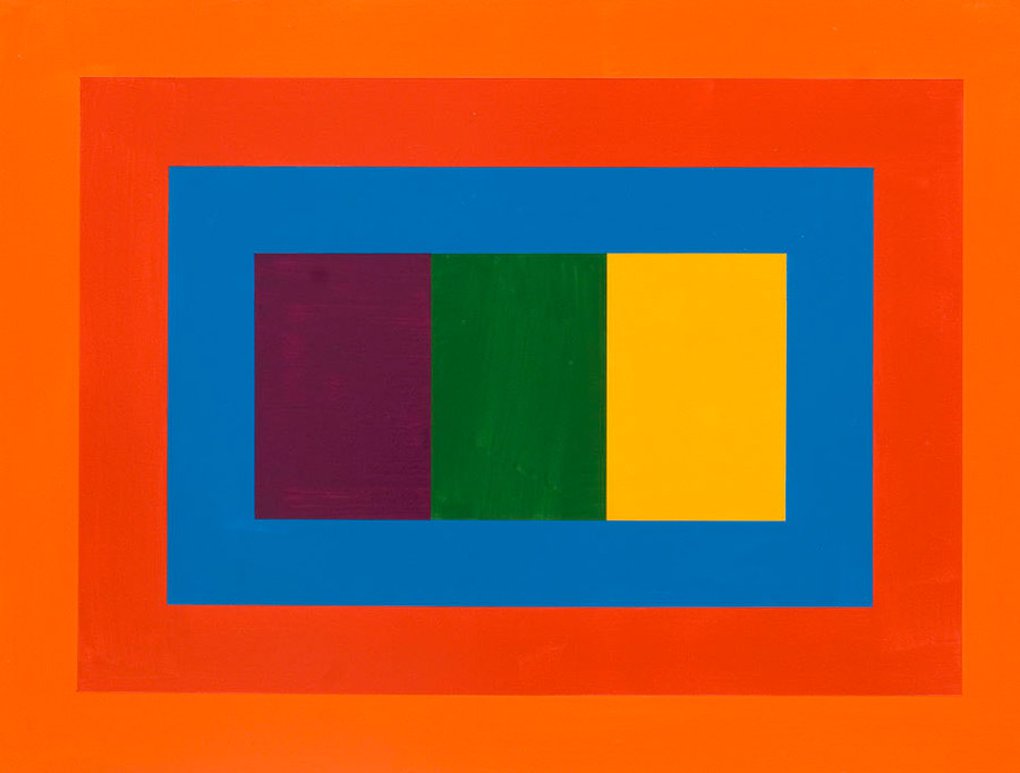

Untitled II, John Nixon

This article was originally published on Brown Bread as 'Rob & Sue Gardiner of The Chartwell Trust, Co-directors / Father and Daughter'

Father and daughter, Rob and Sue Gardiner, are two of five Chartwell Trust directors who are advocating and lobbying for a society that works together to build a movement for a connected creative vision - where art is more than just a passive, pretty thing on the wall.

To spread the word through PHIL about their vision to see visual arts funding taken seriously, Jo Blair sat down with Rob and Sue to talk about how to grow more private and public understandings of the social changes needed.

‟Culture delivers identity, provides inspiration and delivers creative opportunities for everyone. Isn’t this a major aspiration for local and central government?”

The Chartwell Trust was set up by Rob in the early 1970s in order to promote the importance of visual arts and their understanding in the community and to innovatively help fund the building of Hamilton’s first collection-based public art gallery. Since then, it has moved the Chartwell Collection to Auckland Art Gallery (1997), continued to grow it year on year, and supported hundreds of visual artists and projects through the Chartwell Trust’s charitable donations programme.

J: I am personally so inspired by what you have both done for the arts, and I think it’s important that people hear your story. You've shown you really don’t need to be a billionaire to contribute funds to the arts - you can do it in your own way. To kick it off, how did you become interested in the arts?

S: I got involved in utero! My sister Karen and I grew up with two parents whose whole lives were devoted to the arts. As young kids we would sit in their studio in the weekends with our parents - while they did their thing, we had a table set up in the middle with our sketchbooks. We’d sit there drawing, and became inspired and really involved with what our parents were doing.

R: I was also brought up in a family that was influential on the development of my creative interests. Dad was an accountant with lots of creative hobbies. He owned and used an 8mm camera, loved woodwork, collected stamps, and was a clarinettist. My mother was a pianist and a skilled milliner. and I can remember her cutting out dress patterns freehand from fabric on the floor.

Rob and Sue at Christchurch Art Gallery's 'Tangle' installation

J: Where did the idea come from to start a charitable trust that backed visual arts?

R: My wife and I had moved with our young children from Gisborne via the Wairarapa to Hamilton. We joined up with the local Waikato Society of Arts and started participating in art classes and exhibition activities. It was an active and strong amateur arts society with a long history. I believe this participatory kind of activity is important in a community.

As well as advocating for this community group, I became involved in a larger project – with a group advocating for a new public art gallery in the city.

J: Was that the catalyst for your philanthropic work and the beginning of the trust?

R: Yes, it came out of the need to raise funds for the proposed new public art gallery. The group was starting to look to local government and private funding sources which inspired me to think about helping solve the problem of finding the required funds.

J: Would you say, because there wasn’t a long history of private funding for the arts in New Zealand, you needed to be innovative about raising money?

R: Yes, through investment, a bit of luck and the process of generating funds through some innovative projects, it led to the development of the Chartwell Trust. Ultimately, we were successful in our advocacy for the major funding for the building to be provided by the city.

Once the funds for the building of the Gallery came together, it was then time to start thinking about its collection.

‟A public art gallery’s collection provides the public with open access to the creative mind and culture.”

J: How important to you is a city gallery’s collection?

S: A public art gallery’s collection provides the public with open access to the creative mind and culture. It is a tool to reveal the significance of creative thinking to the individual, the community, the country and the world – offering free access to the collections which reflect their identity and greater culture.

R: Many people understand the value of inherited objects in their personal family lives, for example I value the old saws and tools I know my father, grandfather and great grandfather held in their hands and many understand the value of family heirlooms passed down through generations. This is similar to the Māori view of taonga (treasures) as their ancestors, something generations of people feel very deeply. I came to realise that public galleries, owned by municipalities, have the function to collect, preserve, protect these objects and continue to educate and connect the community to them.

Julian Dashper, The Colin McCahons, 1992

‟...public galleries, owned by municipalities, have the function to collect, preserve, protect these objects and continue to educate and connect the community to them.”

J: Who should be funding and nurturing a public art gallery's collection?

R: I think every public gallery needs an appropriate mission statement and ownership responsibilities might best be shared between local and central government. At the moment, this isn’t generally the position. Maybe it’s a matter of sharing the responsibilities involved including funding and governance - this needs to be discussed.

The visual arts have a lot to contribute to the current discussions about the role of culture in determining New Zealand’s future. Culture delivers identity, provides inspiration and delivers creative opportunities for everyone. Isn’t this a major aspiration for local and central government?

J: When does the private individual need to step up and make the difference?

R: While the role for developing a resilient, creative community through cultural investment is the prime responsibility of government, there is a role for some private patronage and advocacy for the arts. Maybe this is a way to understand private and public partnerships?

"The most defining aspect of the next age is that it is a creative age – the world will be shaped by creatively minded citizens developing creative processes and ideas."

J: Do you think it’s possible to convince governments to think creatively?

S: Absolutely, and it’s already happening. There is a lot of international research coming out in recent years that shows that governments are listening to how creative thinking can have a significant positive effect on education, corporate business, health and social well- being and crime statistics. Creative leadership is showing the way and Chartwell is supporting this growing field of knowledge through its funding for the Creative Thinking Project at the University of Auckland.

The most defining aspect of the next age is that it is a creative age – the world will be shaped by creatively minded citizens developing creative processes and ideas.

R: The role of education in public galleries is important – increasingly programmes are reaching out to wider, more diverse communities across a range of age groups and demographics. The value of this needs to be recognised by central government. Coming from these programmes, participants understand their own perceptive and imaginative minds and learn how creative thinking skills are transferable to other aspects of their lives.

S: ... The visual arts enables people to exercise their creative minds, breaking away from traditional linear thinking to new models of generative thought.

R: We inherit the idea that science and arts are opposing disciplines antagonistic to each other. But the best scientists are artists, because they recognise the value of sense based thinking and open-ended enquiry.

‟Part of the problem is that the visual arts are often not understood... Unfortunately, what then builds is a widely-held anti-arts attitude, often driven by the mainstream media looking for sensational headlines and clichéd provocations.”

S: Part of the problem is that the visual arts are often not understood and people may react with frustration when faced with open-ended questions that don't have easy answers, and shy away from the challenge to investigate new ideas. Unfortunately, what then builds is a widely-held anti-arts attitude, often driven by the mainstream media looking for sensational headlines and clichéd provocations. Our education system is not helping either by not prioritising creative thinking in the curriculum.

Bill Culbert, Light Plain, 1997

J: If government funding continues as it is, which doesn't seem to be keeping up with the creative economy, do you think there’s a risk for New Zealand at the moment?

R: I don’t think our society has an understanding of what the risks will actually be. The rapidity of change in particular in the fields of technology and its impact on social structures and attitudes, means that the creative strength of a culture will be even more vital for a future society.

Wider access by more people to creative thinking is essential for our future.

S: We envision a future where New Zealanders are creative producers and this infiltrates through all aspects of society from parents to sportspeople, science and technology, business and entrepreneurship. The arts can then be recognised as the source of creative energy for an innovative New Zealand.

R: If New Zealand gets the model right for arts funding and education as a small country, it could provide leadership to the world. The same way we grow and deliver success in sport. For example, The America’s Cup was the result of a combination of partnerships, but also of minds of science and art coming together to think about how people can form creative units.

Inside Auckland Art Gallery's exhibition 'Shout Whisper Wail! The 2017 Chartwell Show'

J: So, your mission is to advocate and lobby for central government and local government to share in this responsibility. Do you think other people like you are already out there doing this in New Zealand?

R: Yes, and I believe if you deliver this explanation to other like-minded people, more would respond.

‟People are seeking and looking for answers of what the world is going to look like in the future – and private philanthropists and public bodies can actually share in that vision.”

J: And if we can just inspire and grow the funding community, that puts pressure on government to step up as a leader, to compound the wider benefits.

S: Philanthropists contributing to the development of New Zealand as a creative country can dive into particular areas which reflect their own passions. For us, that’s the visual arts because we think that’s the most democratic and most accessible avenue to explore the thinking required.

R: It’s about thinking ahead to the future - what’s going to be important down the track? People are seeking and looking for answers of what the world is going to look like in the future – and private philanthropists and public bodies can actually share in that vision.