Amy's Column 05 - Andrea Zittel at Regen Projects, Beverly Hills, Los Angeles

By Amy Howden Chapman — 19 March 2012

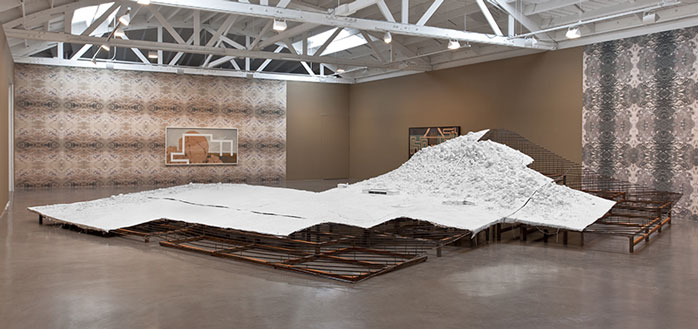

Andrea Zittel, installation view, Regen Projects II, Los Angeles, September 16 – October 29, 2011. Courtesy the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles. Photography by Brian Forrest.

The promise of land was a crucial part of the American dream. People migrated from the Eastern states in search of wider horizons and, by and large, they found them. The land of the West of the US has long been a site for the reinvention of cultural norms. As Marilynne Robinson, the Western born iconic American writer, has written, “I think it was in fact peculiarly Western to feel no tie of particularity to any single past or history, to experience that much underrated thing called deracination, the meditative, free appreciation of whatever comes under one’s eye”[1].

The Landscape of the West and how it is perceived, and changed, through the eye and by the body, was central to Andrea Zittel’s show at Regen Projects, with land viewed from above, afar and in abstract. Land was modelled, rendered in wood and paint and photographed; aerial views of land which had been captured from above were then transformed into kaleidoscopic wallpaper. Land could also be seen in the flesh, with Zittel inviting the public to visit, congregate on her land, drive over it and perform on it.

Occupying the central space of the show was a large model of the particular piece of land that has become the site and central subject of Zittel’s work. The oscillating topography of ‘A-Z West’, named after the land Zittel owns in Joshua Tree, on the dry and mountainous eastern outskirts of Los Angeles, was constructed from plaster laid over hessian laid over a skeletal metal frame, with architectural models of buildings dotting the scene. The sculpture acted like a ghostly version of a visitors’ centre map with the scale and position of the piece allowing viewers to circumnavigate it and take in the natural complexities of the site – boulders, dipping valleys, hills drifting into planes. In some places a lack of surface revealed the model’s underlying metal structure, with these sections signifying where Zittel’s land ownership ceased.

Zittel has acquired the land over time, gradually buying up small adjacent plots. The plots’ irregular shape were determined by laws such as the Homesteading Act which, from 1862, allowed small parcels of federal land to be claimed simply through 5 years of occupation and making improvements. The Act was part of a policy to entice settlement to the western United States. The model revealed the way in which an ideology of property rights has come to define the manner in which the land in the US is formally conceptualised. With the wild geography of the high desert being carved up in rectangles to be sold, subdivided, and resold, eventually each section of land becomes a component of a grid, and the integrity of the natural landscape is diminished.

Zittell’s is a divine viewpoint, from which we look down at the modelled land and it calls to mind military planning – the plotting of troop movements across foreign territory to advance greater political aims. Although Zitell is no ruler she is certainly a leader. Seeing the model of A-Z West from a bird’s eye point of view allows insight into how Zitell might conceptualise land as a forum in which to play out larger ideas of utopian living. It has been a place where she has experimented with structures for living, caravans and sleeping chambers, but it is also a place to make active through presence and process. During the Regen Projects exhibition, another weekend of ‘High Desert Test Site projects’ was held. A good portion of the Los Angeles arts community seemed to disappear on the pilgrimage out to Joshua Tree, returning with many tales including performers dancing in the dirt until collapsing into a car and driving off into the sunset, leaving the audience in their dust.

In ‘Prototype For Billboard at A-Z West: Big Rock on Hill Behind House 2011,’ a figure appears larger than life in paintings that are themselves oversized, each having been painted on a standard piece of plywood. Where blankness or whiteness of canvas might appear in other images, here the wood grain shows through, revealing the materiality of the painting’s structure, knots and grain becoming the figure’s skin or the contours of a rock.

Although we see a body moving through the billboards, we see no face, yet it seems to be Zitell herself as suggested by the figure’s actions which place and hold abstract shapes into and against a desert landscape. A further sign that it is the artist’s image we are witnessing is the presence of one of Zitell’s artist uniforms, a simply stitched smock and top.

Andrea Zittel, installation view, Regen Projects II

A panoply of these uniforms dominates Regen Project’s second gallery space, the outfits appearing like a textile army displayed on a grid of 42 mannequins. For years Zitell has produced a uniform for each season. The outfits seen catalogued together show the passing of time, as felted woollen dresses give way to lighter spring tunics and as a baby bump suddenly has to be accommodated in a uniform of web-like white felt; uniforms for artists are declared to be uniforms also for the work of love and life, including the body’s requirements in the last trimester of pregnancy. While celebrating craft, the uniforms also point to a political dimension behind creating art that is utilitarian. Zitell’s work investigates every layer of living, not least the materials used to insulate and interact with the body. Each material she uses is selected as the best interface between body and land.

Through detailed consideration of the shape and fabric of domestic structures, Zitell’s work highlights the superficiality with which much of suburbia is planned and constructed. As the kaleidoscopic wallpaper declares, much new desert development is repeating patterns, cookie-cutter houses on sprawling streets, all of dubious sustainability. Zitell critiques such modes of development through a resourceful use of materials and an awareness of the local character and unique environmental setting of her own plot of land. In opposition to existing norms, her art exemplifies how life can be organised in sympathy with the land.

Amy Howden-Chapman is an artist and writer born in 1984 in Wellington, New Zealand. She has exhibited widely in Australasia, Europe and the United Stated, and her writing has appeared in publications including, Landfall, Sport, and Natural Selection. In 2011 she graduated from California Institute of the Arts with a Master in Fine Arts. She currently lives and works in Los Angeles, California.

References

- Marilynne Robinson quoted in “West Toward Home:Tracking Marilynne Robinson's intellectual pilgrimage,” by Charles Petersen. Bookforum, Feb/Mar 2012.